For Forty Years, This Was a Thing.

Did you know that poetry, architecture, music, painting, and sculpture were Olympic events? I didn’t until I came across this article at Smithsonian:

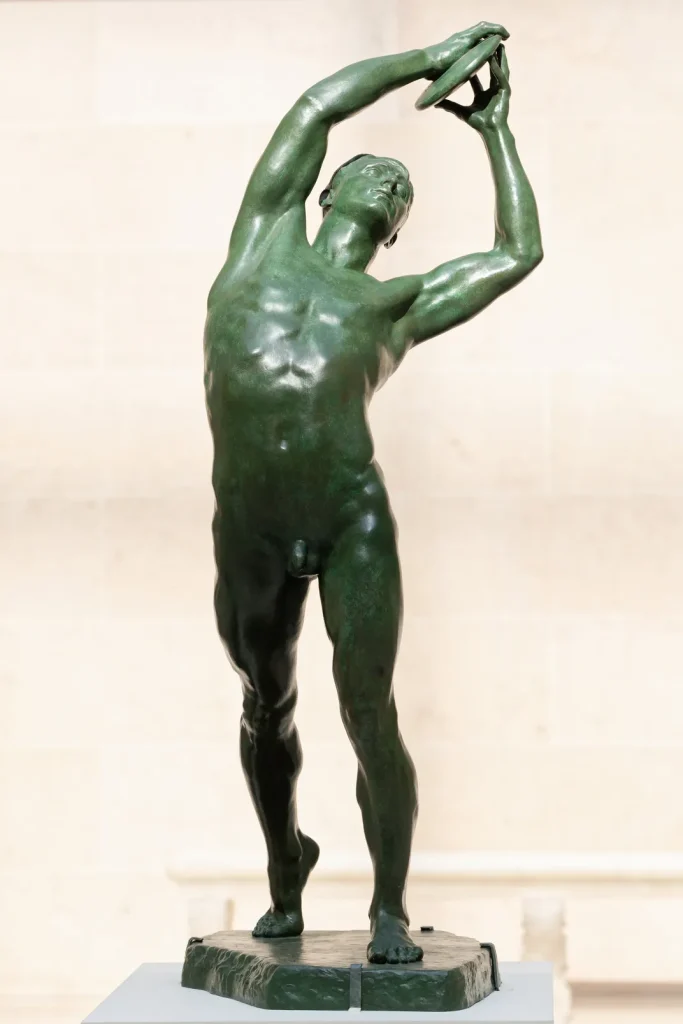

At the ancient Olympics in Greece, athletes weren’t the only stars of the show. The spectacle also attracted poets, who recited their works for eager audiences. Competitors commissioned bigger names to write odes of their victories, which choruses performed at elaborate celebrations. Physical strength and literary prowess were inextricably linked.

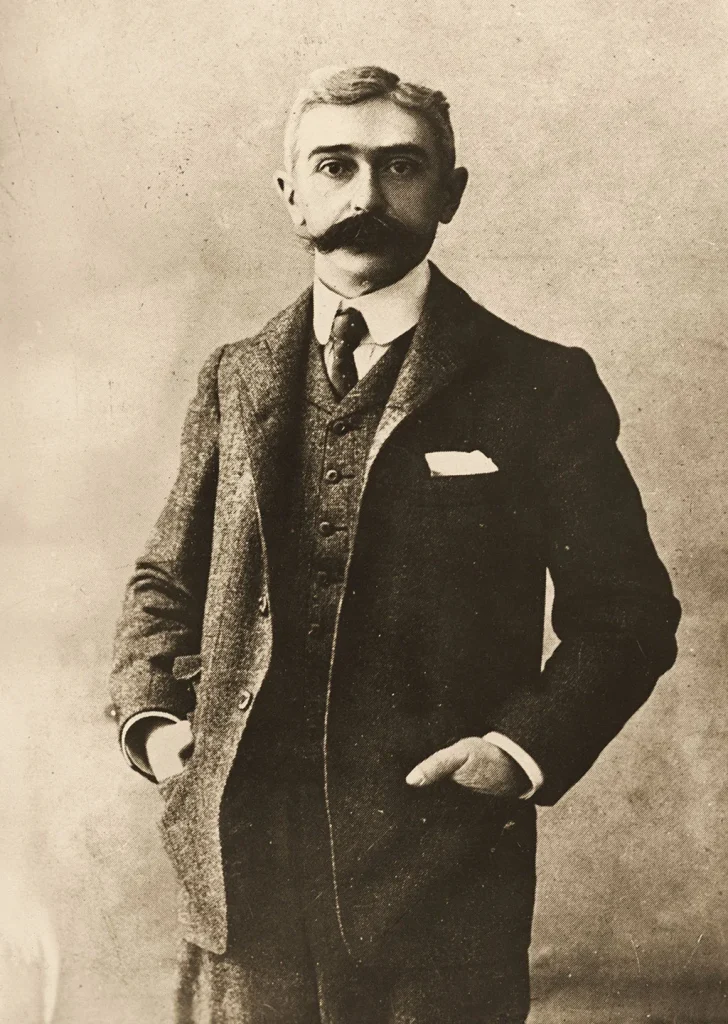

Thousands of years later, this image appealed to Pierre de Coubertin, a French baron best known as the founder of the modern Olympics in 1896. But today’s Games bear little resemblance to Coubertin’s grand vision: He pictured a competition that would “reunite in the bonds of legitimate wedlock a long-divorced couple—muscle and mind.”

The baron believed that humanity had “lost all sense of eurythmy,” a word he used to describe the harmony of arts and athletics. The idea can be traced back to sources such as Plato’sRepublic, in which Socrates extolls the virtues of education that combines “gymnastic for the body and music for the soul.” Poets should become athletes, and athletes should try their hand at verse.

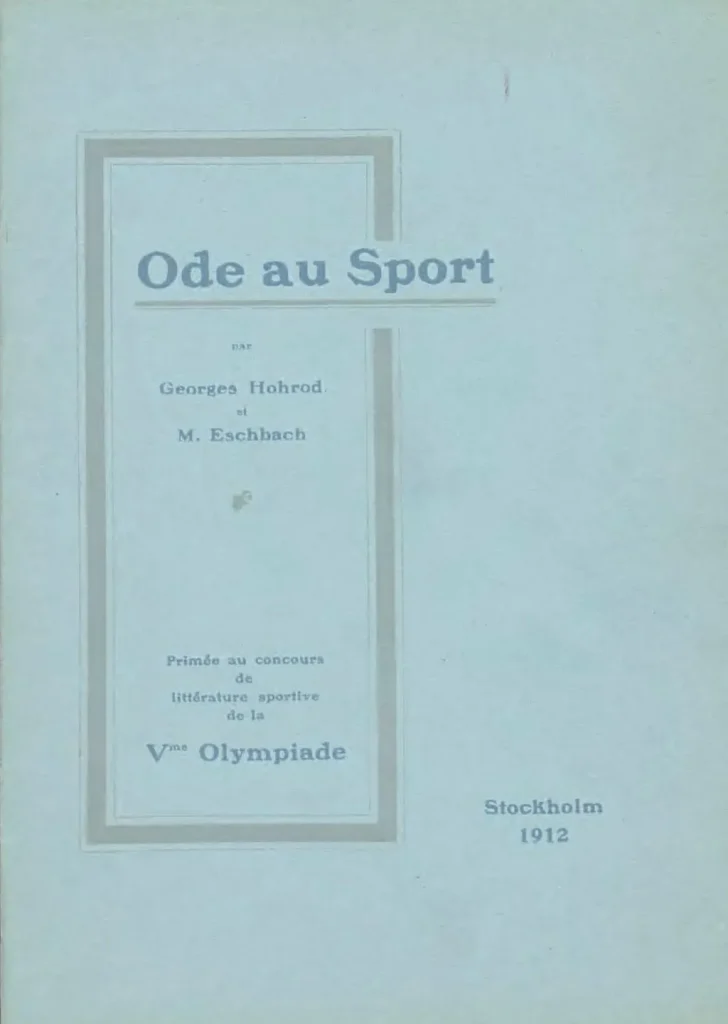

That philosophy was a driving force at the 1912 Stockholm Games, where organizers introduced five arts competitions as official Olympic events. Modern history’s first written work to win an Olympic gold medal was “Ode to Sport,” a prose poem by Georges Hohrod and M. Eschbach. It begins:

O Sport, delight of the Gods, distillation of life! In the grey dingle of modern existence, restless with barren toil, you suddenly appeared like the shining messenger of vanished ages, those ages when humanity could smile.

Okay… I don’t know how simley I would’ve been back then, but sure.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Hohrod and Eschbach understood the spirit of the competition, the fabled marriage of muscle and mind, so acutely. That’s because they were pseudonyms for the man who had conceived the whole idea: The author of “Ode to Sport” was none other than Coubertin himself.

And what about the Painting category? Let’s head over to Apollo Magazine:

Only four painters had entered the first Olympic Art Competition. The best-known of them was Jean-François Raffaëlli, a Frenchman whose works had been shown at the Impressionist exhibitions of 1880 and 1881. Raffaëlli’s painting was admired by Joris-Karl Huysmans and Edgar Degas, but he found no favour with the Olympic judges and was placed last. The winner was Carlo Pellegrini, an Italian best known for his – admittedly rather charming – postcard illustrations of winter sports in the Alps.

…

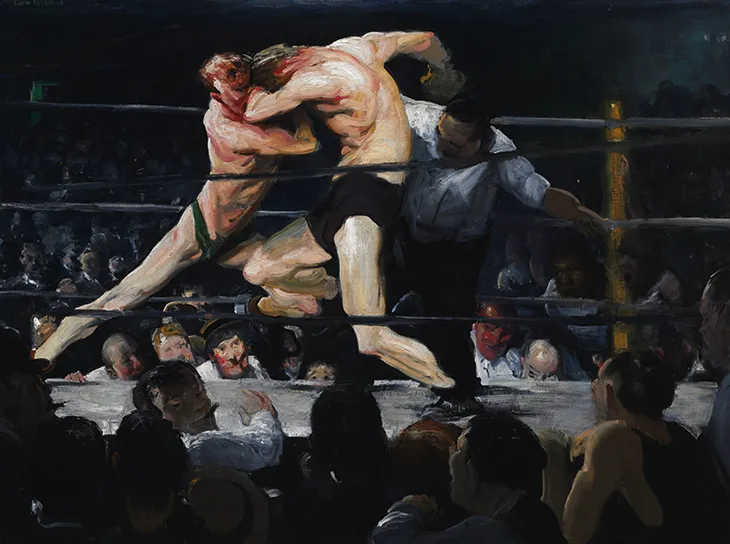

In the 1928 Amsterdam games, for example, the celebrated British equestrian artist Alfred Munnings entered several canvases that failed to impress the judging panel, while a painting of the German heavy-weight boxer Max Schmeling by George Grosz was not deemed good enough to earn the great artist a place on the podium, or even a commendation. At times the judgements were perverse, at others they made sense. It seems unlikely, for example, that the Ashcan artist George Bellows’ painting A Stag at Sharkey’s – entered posthumously and therefore hors concours as one of the ‘amplifying exhibits’ in the exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art – would have been selected for a medal by the panel in Los Angeles, even if it had qualified. Rightly acknowledged today as one of the great masterpieces of sporting art, Bellows’ grimly arresting depiction of a semi-legal bout in a New York fight club, the fighters locked in a desperate struggle as an ugly mob bay for blood, has little to do with the Olympic ideals espoused by Baron de Coubertin.

More from The Smithsonian:

The quality of the arts competitions’ record-keeping was inconsistent, and many of the winning works have “mysteriously vanished, … perhaps, as critics have suggested, because of their dubious literary quality,” wrote Perrottet in a separate 2012 Timesarticle. “Historians have searched in vain for ambitious works like ‘A Rider’s Instructions to His Lover,’ for which the German equestrian poet Rudolf Binding won the silver medal in Amsterdam in 1928, or the French rugby champion Charles Gonnet’s zealous ode to ancient Greek athletes, ‘Before the Gods of Olympia’ (bronze, Paris, 1924).”

…

The Pentathlon of the Muses was part of the Olympics for nearly 40 years, awarding a total of some 150 medals. The events boasted at least a few milestones: While American equestrian Robert Dover is sometimes cited as the first openly gay athlete to compete in the modern Olympics, in 1988, the gay South African poet Ernst van Heerden won a silver medal for lyric poetry exactly 40 years earlier. Still, after the 1948 London Olympics, officials decided to scrap the arts categories.

One particularly strong voice against the arts events was Avery Brundage, who became president of the IOC in 1952. Stanton, author of The Forgotten Olympic Art Competitions, wonders whether Brundage’s opposition was colored by bitterness. “He had entered in the literature category twice,” Stanton told the Los Angeles Times in 2008. “The best he got was an honorable mention.”

Today, the arts medals are no longer listed in official Olympic records. Even now, there are occasional calls to bring the competitions back, but these suggestions have so far fallen flat.

Would you like to see the arts return to the Olympics?