Of Segregation and swimming pools.

“The United States of America,” Heather McGhee writes in the excellent The Sum of Us, “has had the world’s largest economy for most of our history, with enough money to feed and educate all our children, build world-leading infrastructure, and generally ensure a high standard of living for everyone. But we don’t. When it comes to per capita government spending, the United States is near the bottom of the list of industrialized countries, below Latvia and Estonia. Our roads, bridges, and water systems get a D+ from the American Society of Civil Engineers. With the exception of about forty years from the New Deal to the 1970s, the United States has had a weaker commitment to public goods, and to the public good, than every country that possesses anywhere near our wealth.

‘Observers have tried to fit multiple theories onto why Americans are so singularly stingy toward ourselves: Is it a libertarian ideology? The ethos of the western frontier? Our founding rebellion against government?”

McGhee pointedly and poignantly makes the case that biggest reason is racism. When I read her book not too long after its release, I found myself taken aback. Not by the scope or depth of such bigotry (I mean, sad, but um, duh), but rather how petty it could be. And how that pettiness resided on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. Specifically when she mentions Elizabeth, NJ, the city bordering my hometown of Linden, where I also spent seven years attending a now-defunct, private Christian school as a kid. Oh, and moved to in my mid-twenties. It’s not that this part of NJ is a racial utopia (I’m looking at you, Clark), but Elizabeth? Yes, Elizabeth.

In the fascinating book Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, author Jeff Wiltse writes about a harrowing series of events that occurred in the fourth most populous city in the Garden State:

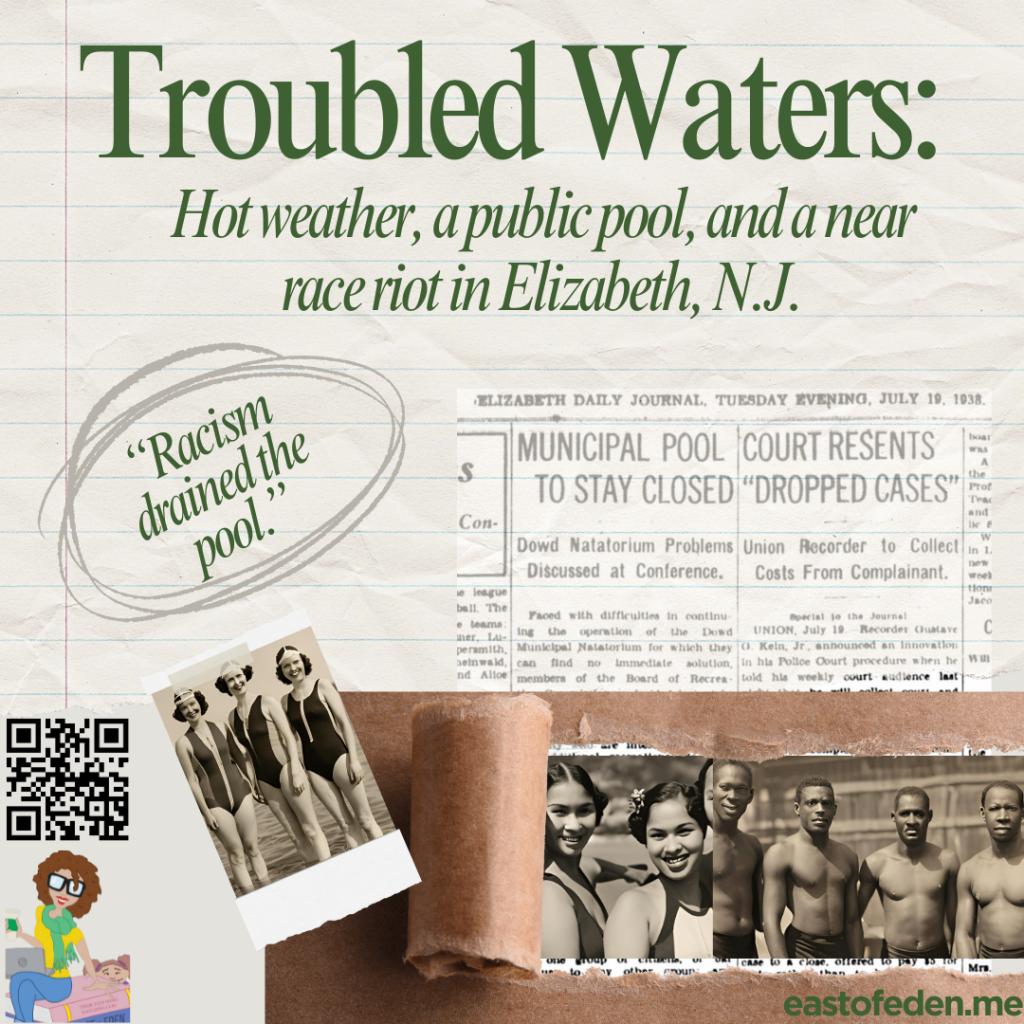

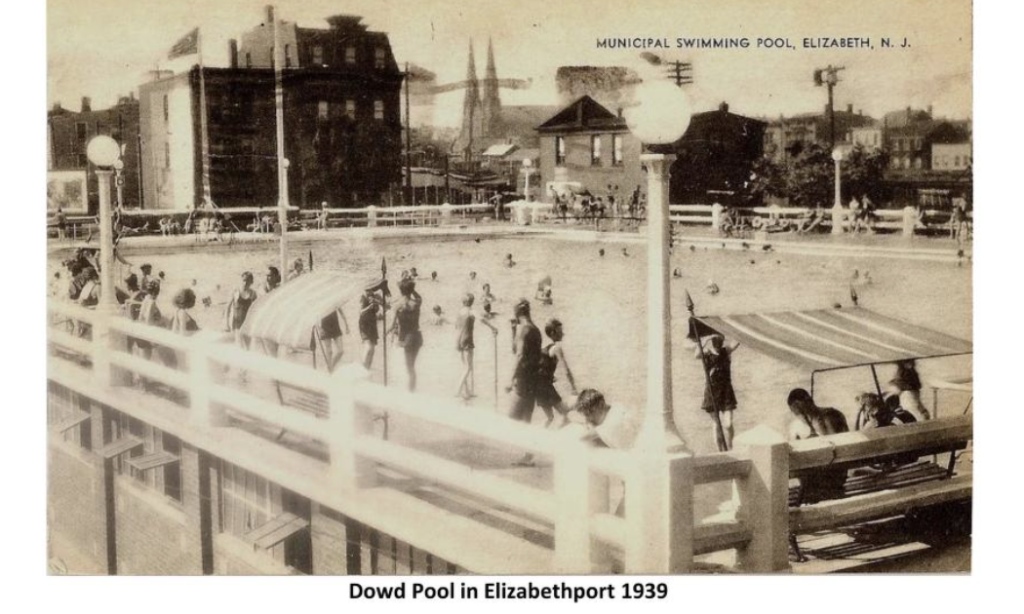

When the city opened its first pool in 1930,city officials refused to admit black residents, even though blacks and whites had bathed together at the city’s river bath. Unaccustomed to such blatant public forms of discrimination, local NAACP officials protested black residents’ exclusion from Dowd Pool. They met with Elizabeth’s Recreation Commission just days after the pool opened in order to resolve what the commission called “the bathing problem for the colored people.” After a long discussion, commission president James O’Neill “informed the Colored Delegation that the Supt. will be given full instructions in the morning to allow the colored people the use of the swimming pool at all times.” City officials obviously did not want blacks to swim in Dowd Pool with whites, but they would not brazenly violate New Jersey’s civil rights law, which prohibited racial discrimination at public facilities.

The integration order marked the end of official racial exclusion at Dowd Pool and the beginning of harassment and violence. Two days later, three teenagers tested the new policy. Allen Chase approached the ticket booth alone at about three o’clock but was arrested for disorderly conduct before passing through the gate. The admission attendant claimed that Chase had refused to pay the standard ten-cent admission fee and threatened to beat him up if not admitted for free. Chase vehemently denied the accusation, claiming that he merely inquired whether it was true that blacks would be admitted to the pool and then intended to run home and get his swimming suit. The police officer stationed at the pool arrested him nonetheless.

An hour later, Morgan Dickinson and Walter Gordon paid their ten cents, showered, but never made it into the water. Another attendant, Thomas Keating, stopped the two teenagers as they exited the locker room and admonished them for not taking a shower. While Dickinson and Gordon were assuring Keating that they had in fact showered, a group of white swimmers appeared atop the staircase leading up to the pool and threatened to pummel the two teenagers if they attempted to enter the water. Sensing trouble, Patrolman Newallis, the same officer that had arrested Chase, “advised the colored youths not to make use of the pool.”

Undeterred, the young men cited the recreation commission ruling giving them equal access to the pool and then returned to the locker room to shower again. When they finally ascended the stairway, Dickinson and Gordon encountered dozens of “menacing swimmers” standing shoulder-to-shoulder blocking their access to the pool. According to the Elizabeth Daily Journal, they were then “somewhat roughly handled by the crowd.” Dickinson and Gordon finally managed to escape after fourteen more police officers arrived to restore order. The officers arrested one of the white assailants, thirty-four-year-old Michael

“Capko, and charged him with inciting to riot. The next morning, Allen Chase and Capko were both arraigned in Police Court. Chase was fined ten dollars for allegedly threatening the pool attendant, and Capko five dollars for leading the assault on Dickinson and Gordon.47 The message to black residents was clear: if you try to swim in Dowd Pool, you will be arrested on trumped-up charges or pummeled by white swimmers. Both forms of intimidation effectively deterred black residents from using the pool for several years.

Then, on July 6, 1938, several young men approached Dowd Pool, paid their admission, showered, and actually entered the water. They were the first identifiably black people to swim in Dowd Pool, eight years after it opened. It is not clear what prompted the young men to seek entry after so many years of whites-only use. Their presence in the pool did not go unnoticed. According to a recreation department official, they were “subjected to certain petty annoyances at the hands of white bathers.” The white swimmers “ducked” the youths by holding them underwater, shouted threats at them, and poured buckets of water into the lockers where they had left their clothes. The young men left the pool wet, bruised, and perhaps even short of breath. And yet this time, they would return.

Over the next two weeks, ordinary black citizens—many of them teenagers and children—courageously integrated Dowd Pool. Knowing that they would be assaulted and perhaps arrested, they nonetheless returned to the pool day after day. Every black swimmer that entered the water quite literally risked his or her life. Swimming pools were inherently dangerous places even under ideal circumstances. At Dowd Pool during the summer of 1938, black swimmers also had to contend with fellow swimmers dunking and punching them. Furthermore, the safety net for endangered swimmers, the lifeguards, offered no assistance. Despite the risks, more and more black swimmers came to the pool and endured the threats, assaults, and other “petty annoyances.” When white swimmers found that violence no longer intimidated blacks from using the pool, many stopped coming. White attendance plummeted to one-tenth its normal level. The dislocated white swimmers redirected their threats and vitriol at city officials. They sent scores of “abusive” letters to the mayor and Recreation Commission promising widespread racial violence if the city did not bar blacks from entering the pool. City officials responded in the press that they could not officially segregate the pool. They could, however, close it, which is what they did. The official explanation was that attendance had sunk so low that the pool was no longer economical to operate. The fact that most of the swimmers were now black probably made the decision easier.

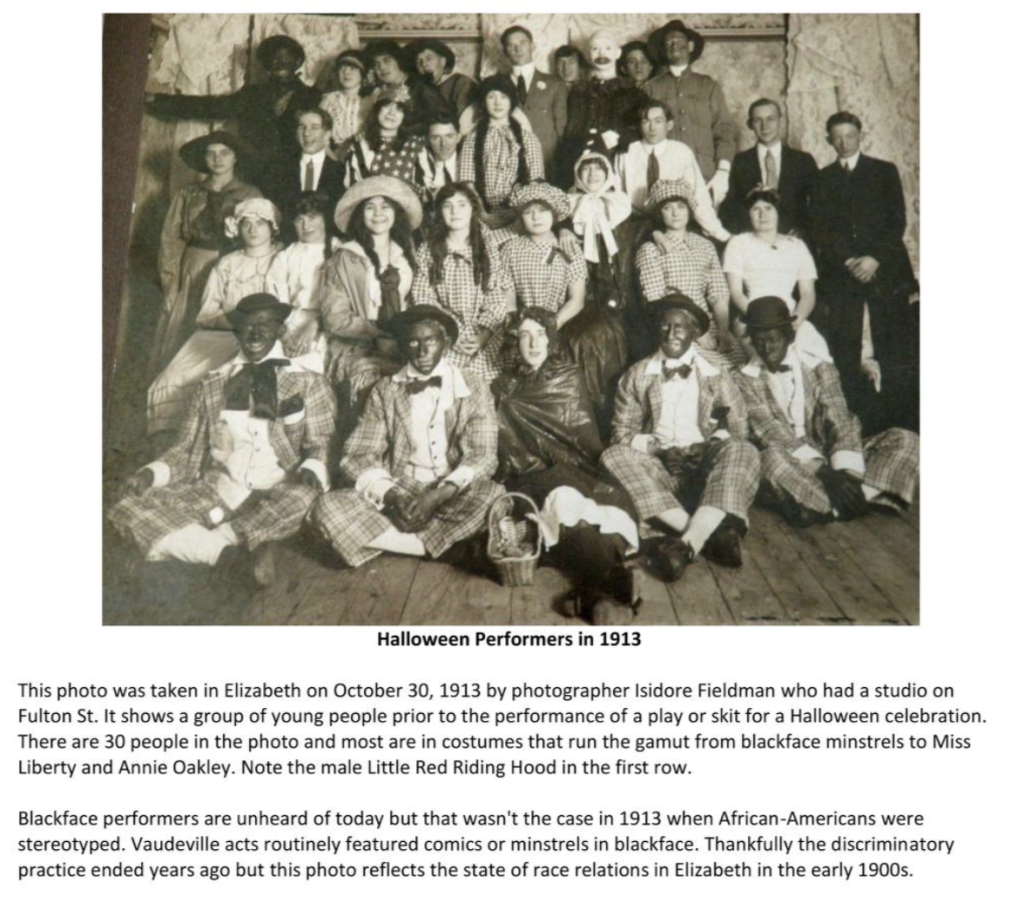

Sadly, those racist White Elizabethans preferred the pool be shut down altogether rather than simply share with Black neighbors. While looking through Mr. Baptista’s book, I came across this:

Elizabeth, like the rest of the North, was steeped in racism, even though it operated differently than in the South.

More Contested Waters:

When Dowd Pool opened for the 1939 swimming season, the social use had, apparently, returned to whites only. The evidence to support this conclusion is circumstantial yet compelling. Whereas the racial conflicts the previous summer were widely reported in the local newspaper and commented upon regularly in city council meetings, no mention of racial issues at the pool appeared in either of these sources. Perhaps most convincing, the attendance at Dowd Pool returned to the level of pre-1938 summers. During its first eight years of whites-only operation, attendance averaged around 70,000 swims per summer. During the brief periods of truly integrated swimming, it dropped to between one-quarter and one-half normal use. In 1939, however, total attendance rebounded to 63,612.53 Either white people in Elizabeth suddenly overcame their racial prejudices, stopped abusing black swimmers, and willingly swam in the same pool with them, or, more likely, the city’s black population decided that a swim in Dowd Pool was not worth the threat to their safety.

I’ll close the post with a story from Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson that exemplifies the emotional turmoil and pain that such heinous actions inflicted on Black people, especially kids, in the century after the Fourteenth Amendment became law.

View this post on Instagram

“It was in this atmosphere, in 1951, that a Little League baseball team in Youngstown, Ohio, won the city championship. The coaches, unthinkingly, decided to celebrate with a team picnic at a municipal pool. When the team arrived at the gate, a lifeguard stopped one of the Little Leaguers from entering. It was Al Bright, the only black player on the team. His parents had not been able to attend the picnic, and the coaches and some of the other parents tried to persuade the pool officials to let the little boy in, to no avail. The only thing the lifeguards were willing to do was to let them set a blanket for him outside the fence and to let people bring him food. He was given little choice and had to watch his teammates splash in the water and chase each other on the pool deck while he sat alone on the outside.

“From time to time, one or another of the players or adults came out and sat with him before returning to join the others,” his childhood friend, the author Mel Watkins, would write years later.

It took an hour or so for a team official “to finally convince the lifeguards “that they should at least allow the child into the pool for a few minutes.” The supervisor agreed to let the Little Leaguer in, but only if everyone else got out of the water, and only if Al followed the rules they set for him.First, everyone—meaning his teammates, the parents, all the white people—had to get out of the water. Once everyone cleared out, “Al was led to the pool and placed in a small rubber raft,” Watkins wrote. A lifeguard got into the water and pushed the raft with Al in it for a single turn around the pool, as a hundred or so teammates, coaches, parents, and onlookers watched from the sidelines.

After the “agonizing few minutes” that it took to complete the circle, Al was then “escorted to his assigned spot” on the other side of the fence. During his short time in the raft, as it glided on the surface, the lifeguard warned him over and over again of one important thing. “Just don’t touch the water,” the lifeguard said, as he pushed the rubber float. “Whatever you do, don’t touch the water.”The lifeguard managed to keep the water pure that day, but a part of that little boy died that afternoon. When one of the coaches offered him a ride home, he declined. “With champion trophy in hand,” Watkins wrote, Al walked the mile or so back home by himself. He was never the same after that.

Despite the blatant discrimination, Al Bright turned out okay. More than okay.